Try This Experiment on Your Baby!

Project name:

False Positives, False Negatives

Age range:

15 to 20 months

Research area:

Social and emotional development

Like this experiment?

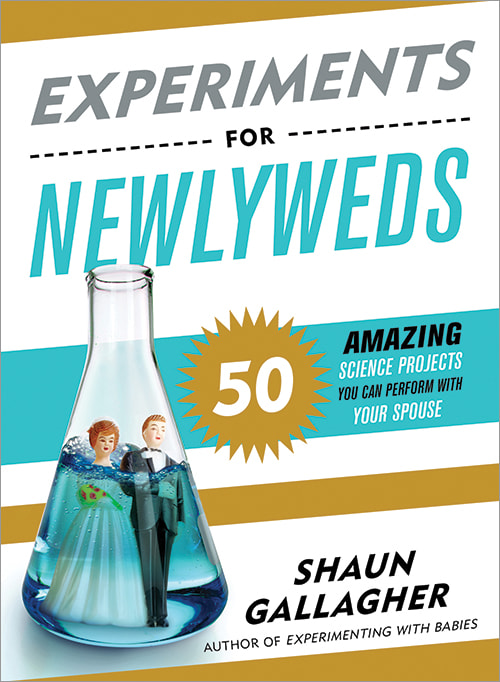

Buy "Experimenting With Babies," which contains 50 other fascinating science projects you can perform on your kid. It makes a great gift for new parents!